H.G. Lewis: The Monster A Go-Go Interview

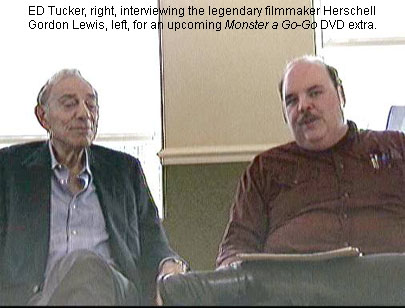

When Bill Rebane discovered that I would be crossing paths with Herschell Lewis again this past March at the Gasparilla Film Festival in Tampa, he jumped on the opportunity. He already had plans in the works for a special DVD release of Monster A Go-Go, the resurrected version of a film he started as Terror at Half Day. In addition to working as a cameraman on the original shoot, Lewis was also responsible for salvaging what was shot, assembling it into a feature, and getting it into theaters several years later. The following interview is an abridged version of the one I taped, at Bill Rebane’s request, as a potential extra for the DVD release.

When Bill Rebane discovered that I would be crossing paths with Herschell Lewis again this past March at the Gasparilla Film Festival in Tampa, he jumped on the opportunity. He already had plans in the works for a special DVD release of Monster A Go-Go, the resurrected version of a film he started as Terror at Half Day. In addition to working as a cameraman on the original shoot, Lewis was also responsible for salvaging what was shot, assembling it into a feature, and getting it into theaters several years later. The following interview is an abridged version of the one I taped, at Bill Rebane’s request, as a potential extra for the DVD release.

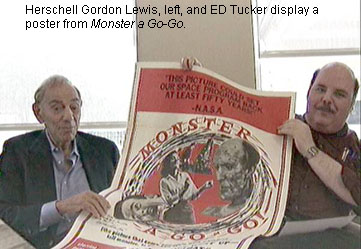

ED Tucker: Greetings ladies and gentlemen, my name is ED Tucker. I am an author and film historian and with me is Mr. Herschell Gordon Lewis. We’re here today to talk about one of the films Mr. Lewis picked up for release as a second feature. It was originally released as Monster A Go-Go and I have one of the posters here that may bring back some memories.

Herschell Lewis: It certainly does! Where did you get that?

ET: It may be the last one in existence!

HL: You talk about a collector’s item!

ET: You were kind enough to autograph this for me “To Ed, who understands this picture better than I do”. Bill Rebane was also kind enough to autograph it and he signed it “To Ed, I knew exactly what was going on with this picture before Herschell Lewis got it”!

HL: A true collector’s piece.

ET: Now Monster A Go-Go originally started life as a film called Terror at Half Day.

HL: Half Day, most people don’t know anything about it. Half Day is a little town North West of Chicago, about forty miles I would guess. I don’t know why Bill gave it that title but I felt for a more generalized release we needed a more substantial title.

ET: In a nutshell, Bill started making this film and got about 90% of the way done shooting it and ended up losing funding for it. It ended up in the lab and somewhere around 1965 you found it when you were looking for a second feature.

HL: Yes, I needed a second half to go along with a movie I had made called Moonshine Mountain. At that time, the drive-in theaters were the best risks for our money. In order to control film rentals, one had to have both sides of the double feature. If you only had one picture, they would throw another picture in against yours and invariably tell both producers “Oh, well the other picture was the key feature and gets the percentage. Your feature only gets a flat amount of money.” A person who came in with both sides of the double feature didn’t have to face that problem. I needed another movie because I only had one.

HL: Yes, I needed a second half to go along with a movie I had made called Moonshine Mountain. At that time, the drive-in theaters were the best risks for our money. In order to control film rentals, one had to have both sides of the double feature. If you only had one picture, they would throw another picture in against yours and invariably tell both producers “Oh, well the other picture was the key feature and gets the percentage. Your feature only gets a flat amount of money.” A person who came in with both sides of the double feature didn’t have to face that problem. I needed another movie because I only had one.

ET: That was when you remembered that this film had never been completed?

HL: I think the lab helped jog my memory a little on it. It wasn’t completed. In fact, one of the problems we had with the movie was that somebody had cut the slates off. In order to synch up the sound, they would normally say “Scene 27, take 2” and clap the slate. On the soundtrack you would hear it and on the picture you would see it. You would match those two up and the voices come out in synch. These slates had been cut off so we had to synch it all up by eye!

ET: Was that a big problem?

HL: Not a big problem, it certainly wasn’t the first time that had happened.

ET: Do you recall exactly how complete the film was when you got it and what you had to do to make it into a feature?

HL: It was a lot of footage. I think Bill had shot about 80,000 feet of black and white film on this but I couldn’t make it convert into a feature. I shot about a thousand feet of footsteps, hands opening a book, and somebody talking on the telephone just to flesh this thing out and so the plot I substituted for his original would make some sense.

ET: So you actually had to change the plot of the film? Do you recall what the original plot was?

HL: The original plot was somewhat similar. An astronaut went up and a monster came down. Bill Rebane had a fellow named Henry Hite, a gentle giant I guess you would call him, who played the part of the monster. Henry Hite was part of an old Vaudeville act called Lowe, Hite, and Stanley. Lowe was a midget, Hite was a giant, he was about seven and a half feet tall, and Stanley was an ordinary guy. As I heard the story,Stanley disappeared, the one person who was easily replaced, but the act disappeared too. Henry Hite was rather elderly then and living in a little hotel in Chicago. He had reached a point where his ankles barely supported him but he was always willing and good natured. We changed the plotline from a serious kind of thing because I felt the special effects were not competitive with what other companies were doing showing astronauts going up and monsters coming down. We changed it into a sort of satire. That was the change I made and the campaign reflects that.

ET: Did you bring Henry Hite back in to film any additional footage?

HL: No, I didn’t. I only filmed footsteps, books, telegrams, stuff that didn’t require talent! I had been the cameraman, as you may recall, for some of this picture when it was originally shot. The movie, as I remember, was shot spasmodically, from time to time, as financing became available. I recall shooting under Wacker Drive in Chicago where traffic was just going by us! One sunny afternoon in Lincoln Park, I remember hand holding the camera and pretending I was the monster by rocking the camera back and forth while walking forward.

ET: Do you recall a scene where you blocked off Michigan and Oak Street?

HL: I don’t remember that one but it doesn’t seem unusual. We often did that. We were assumptive filmmakers. Dave Friedman, who is the master of assumption, pointed out, and I think very correctly, that when you ask for permission you are asking for a no. When you show up with a big Mitchell camera, which is what we had, the appearance of it gave you cache before you shot a foot of film and often times all people would say was “What can we do to help?”

ET: Was this a union picture when you shot it?

HL: It couldn’t have been if I was on the camera for part of it. I know Bill Rebane had some union people there. As I recall his stuntman belonged to some kind of union, I’m rather vague on this, but there was some kind of conversation on what hours he could work.

ET: I think when Bill Rebane started the picture it had a union crew.

HL: He started it as quite a sophisticated picture. He had second level Hollywood names in there. There was an actress named June Travis who had appeared in a number of legitimate B movies.

ET: I believe at one point in time Ronald Reagan was actually attached to this picture. Fortunately, somewhere along the way he got out of acting and into politics instead.

HL: That depends on what your politics are!

ET: Do you recall working with a gentleman by the name of Bill Johnson?

HL: Oh sure, Bill Johnson was a friend of both Bill’s and mine. Bill was kind of like we were, a film bum I guess, in Chicago. He was a treasure house of old, obsolete, equipment. Whenever something would blow out and we would say oh gosh, even the Smithsonian Institute doesn’t have one of these, Bill Johnson would have it! He was a wonderful, good natured and very giving kind of person.

HL: Oh sure, Bill Johnson was a friend of both Bill’s and mine. Bill was kind of like we were, a film bum I guess, in Chicago. He was a treasure house of old, obsolete, equipment. Whenever something would blow out and we would say oh gosh, even the Smithsonian Institute doesn’t have one of these, Bill Johnson would have it! He was a wonderful, good natured and very giving kind of person.

ET: Is there anything else you remember about the film or working with Bill Rebane that you would like to share?

HL: Bill was a very nice man. We first met at the old United Film and Recording Studio in Chicago. He was a recent arrival in the United States and represented a company called Cinetarian which was sort of the precursor of first Cinerama and then later, I guess, IMAX. We watched this footage that he had brought with him as an example. I remember lying on our backs and looking at the ceiling. The whole ceiling was filled with this Cinetarian movie but nothing ever came of it.

ET: Do you have any idea how this film has developed such a cult following?

HL: I don’t understand that about any movie, really. It’s a piece of entertainment and often times a movie that becomes a cult movie is one in which the least amount of money was spent. You don’t find Star Wars coming out as a cult film. It’s something on a different plateau. A movie like this where people say “I can’t believe they actually did this” has a better chance of becoming a cult film.

ET: Mr. Lewis, thank you very much for being with us here today to discuss Monster A Go-Go.

HL: It’s a pleasure!