The Yellow Submarine Chronicles Part Four: It’s All In The Mind Y’Know!

The credits for Yellow Submarine attribute the screenplay for the film to four writers. According to various accounts though, the number of contributors to the story that eventually found its way to the screen could be as high as forty! In a 1999 interview, producer Al Brodax put the number of completed scripts for Yellow Submarine at no less than fourteen! Adding to the confusion is the fact that the “final” version of the screenplay never existed until several months after the film was released. Two things are certain though, there were more people involved in the creation of the story than those who received credit for it and the extent of the contributions of the credited writers will probably always be in dispute.

The whirlwind nature of Yellow Submarine’s production necessitated the use of multiple writers just to meet the scheduling deadlines. The Beatles’ decree of distinction between the film and the King Features cartoon series limited the choice of immediately available writers who were a known quantity and further complicated the already seemingly impossible task. When the film was finally completed and screened for audiences, the writing acknowledgements listed four individuals – Lee Minoff, Jack Mendelsohn, Erich Segal, and Al Brodax.

In 1967, Lee Minoff, the younger brother of magazine writer Charles Minoff, was a practicing psychologist with an interest in following in his brother’s footsteps. He was a member of the Beatles’ generation, fresh out of college, and in tune with the times. Al Brodax chose Minoff as the original writer for the film almost out of desperation to keep the project from tanking. The, as yet untitled, animated film had not been given a green light at this point by either the Beatles or their manager, Brian Epstein, and it would remain that way until Brodax could prove he could produce a script that would appeal to more than a Saturday morning audience. Lee Minoff pitched the idea to Brodax of a story built around the Beatles’ song Yellow Submarine (perhaps inspired by the suggestion from Ringo Starr). Following a meeting with Paul McCartney, Minoff spent a weekend writing in a London hotel room under the watchful eye of Al Brodax. He created the original story treatment for the film which outlined the basic elements of the plot (including the characters of Old Fred and the Boob and the concept of multiple seas) which was approved by McCartney and gained Brodax the go ahead with United Artists. Minoff expanded his treatment into a script but unfortunately, according to Brodax, the majority of it was unusable.

In 1967, Lee Minoff, the younger brother of magazine writer Charles Minoff, was a practicing psychologist with an interest in following in his brother’s footsteps. He was a member of the Beatles’ generation, fresh out of college, and in tune with the times. Al Brodax chose Minoff as the original writer for the film almost out of desperation to keep the project from tanking. The, as yet untitled, animated film had not been given a green light at this point by either the Beatles or their manager, Brian Epstein, and it would remain that way until Brodax could prove he could produce a script that would appeal to more than a Saturday morning audience. Lee Minoff pitched the idea to Brodax of a story built around the Beatles’ song Yellow Submarine (perhaps inspired by the suggestion from Ringo Starr). Following a meeting with Paul McCartney, Minoff spent a weekend writing in a London hotel room under the watchful eye of Al Brodax. He created the original story treatment for the film which outlined the basic elements of the plot (including the characters of Old Fred and the Boob and the concept of multiple seas) which was approved by McCartney and gained Brodax the go ahead with United Artists. Minoff expanded his treatment into a script but unfortunately, according to Brodax, the majority of it was unusable.

The Minoff script may have been rejected, but enough of his ideas were retained to get the animators moving forward on isolated segments of the film like the Liverpool sequence. As the desperation grew, Brodax turned to an assistant professor at Yale University, Erich Segal, for a workable script they could actually use. In an attempt to minimize any further risks to the production, Al Brodax involved himself personally this time. According to his version of the facts, Brodax spent three weeks with Erich Segal sequestered in a London hotel room writing day and night, almost nonstop. The Brodax/Segal script fleshed out some of Minoff’s concepts and also incorporated contributions from other members of the production team. As time became critical, sequences and entire characters the pair envisioned had to be jettisoned in the interest of completing the film on schedule. By the end of the three weeks and with a few subsequent weekend rewrites, the production finally had something resembling a script even if it wasn’t completely finished.

Working almost simultaneously with, and exclusively from, the Brodax/ Segal team, was Jack Mendelsohn, a veteran of the Beatles cartoon series as well as many other King Features animation projects like the Beetle Baileyand Popeye cartoons. While the Beatles would have certainly balked had they known of his involvement, Brodax tapped him to write a script after the Fab Four had left for India and lost interest in the film. Mendelsohn was currently employed by Hanna-Barbera and had a reputation in the industry for being able to deliver a linear story in a short period of time. Over the course of two weeks, working from his home in California, he delivered his own take on the story based on

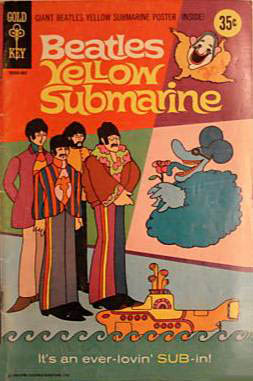

Working almost simultaneously with, and exclusively from, the Brodax/ Segal team, was Jack Mendelsohn, a veteran of the Beatles cartoon series as well as many other King Features animation projects like the Beetle Baileyand Popeye cartoons. While the Beatles would have certainly balked had they known of his involvement, Brodax tapped him to write a script after the Fab Four had left for India and lost interest in the film. Mendelsohn was currently employed by Hanna-Barbera and had a reputation in the industry for being able to deliver a linear story in a short period of time. Over the course of two weeks, working from his home in California, he delivered his own take on the story based on  the other drafts that had been submitted. While the Mendelsohn script also contained ideas that had to be aborted, he did contribute the concept of the war with the Blue Meanies (originally called the Monstrous Blues), the personality characteristics for each of the Beatles, and the Sea of Holes. The comic book adaptation of the film (published by Gold Key in 1968), which varies considerably from its source material, appears to have been largely derived from Mendelsohn’s story.

the other drafts that had been submitted. While the Mendelsohn script also contained ideas that had to be aborted, he did contribute the concept of the war with the Blue Meanies (originally called the Monstrous Blues), the personality characteristics for each of the Beatles, and the Sea of Holes. The comic book adaptation of the film (published by Gold Key in 1968), which varies considerably from its source material, appears to have been largely derived from Mendelsohn’s story.

Aside from the four credited authors, several other writers had input into the screenplay ranging from a few creative touches to full revisions of the script. Production designer Heinz Eddelmann is generally credited for creating the various Blue Meanie characters that served as the villains of the plot. Roger McGough, an English poet, polished the film’s dialog to give it a more authentic Liverpool sound. Animators on the project, such as Charlie Jenkins and George Dunning, created entire sequences from beginning to end with no input from any of the official screenwriters. Legend has it that at one point during production, Edelmann and unit director Bob Balser went through all the different drafts and cobbled together the most coherent version of a script they could from all the pieces. As the film neared completion, it became evident that even with all of these contributions there was still no cohesive ending to the picture. Lacking both time and money, the production staff assembled leftover artwork and unused samples to create the stilted but still inspired It’s All Too Much sequence that caps the film.

Aside from the four credited authors, several other writers had input into the screenplay ranging from a few creative touches to full revisions of the script. Production designer Heinz Eddelmann is generally credited for creating the various Blue Meanie characters that served as the villains of the plot. Roger McGough, an English poet, polished the film’s dialog to give it a more authentic Liverpool sound. Animators on the project, such as Charlie Jenkins and George Dunning, created entire sequences from beginning to end with no input from any of the official screenwriters. Legend has it that at one point during production, Edelmann and unit director Bob Balser went through all the different drafts and cobbled together the most coherent version of a script they could from all the pieces. As the film neared completion, it became evident that even with all of these contributions there was still no cohesive ending to the picture. Lacking both time and money, the production staff assembled leftover artwork and unused samples to create the stilted but still inspired It’s All Too Much sequence that caps the film.

Too many cooks may spoil the soup but the final stew that is Yellow Submarine is a delicacy all its own. Numerous articles have been written and portions of books have been dedicated to trying to sift through the varying stories (no two of which are in complete agreement) and determine exactly who contributed what. In an interview around the time of the film’s 30th anniversary, Erich Segal (who went on to write Love Story) was quoted as saying “I don’t want to enter into this silly discussion (of who contributed what). I wrote some, Tom Stoppard (a famous playwright who delivered an early draft) wrote some, God knows who else slipped in a word or two. And maybe Lee Minoff wrote some”. Even the guys who wrote it don’t know for sure!

Too many cooks may spoil the soup but the final stew that is Yellow Submarine is a delicacy all its own. Numerous articles have been written and portions of books have been dedicated to trying to sift through the varying stories (no two of which are in complete agreement) and determine exactly who contributed what. In an interview around the time of the film’s 30th anniversary, Erich Segal (who went on to write Love Story) was quoted as saying “I don’t want to enter into this silly discussion (of who contributed what). I wrote some, Tom Stoppard (a famous playwright who delivered an early draft) wrote some, God knows who else slipped in a word or two. And maybe Lee Minoff wrote some”. Even the guys who wrote it don’t know for sure!